- The Women’s Professional Baseball League is holding tryouts ahead of its inaugural 2026 season.

- Committed players include history-makers including Kelsie Whitmore and Mo’Ne Davis.

- ‘We’re finally being seen,” Whitmore says of the WPBL.

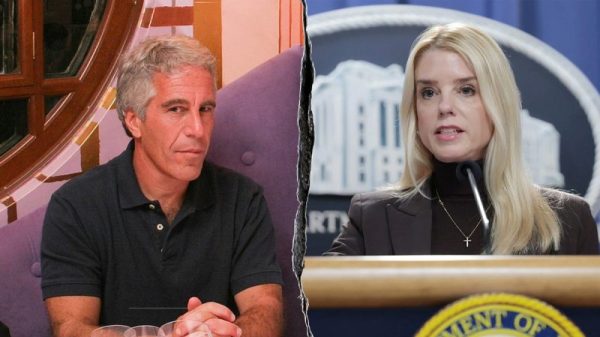

For one of the few times in her more than decade-long baseball career, Kelsie Whitmore doesn’t have to worry about creating her own path.

At 27, she has experienced an entire spectrum of emotional highs and lows in her quest to simply play ball, from assimilating with all the boys on her high school baseball team, to a significant diversion from the path forcing her into college softball, to the trailblazing glory, but also the punishing loneliness, of being the first woman to play alongside former and current big leaguers in the independent Atlantic League.

So perhaps it will feel a little strange when Whitmore reports Aug. 22 for tryouts with the Women’s Professional Baseball League, which is staging four days of evaluations in Washington, culminating at Nationals Park on Aug. 25, setting the stage for the league’s first player draft in October ahead of its inaugural 2026 season.

Whitmore will see so many familiar faces among the 600 players registered for tryouts, such as her teammates on the U.S. Women’s National Team who are the backbone of this tight-knit yet often overshadowed community. And she’ll also see players young enough to have drawn inspiration from her and, in turn, will inspire the next generation.

The logistics and uncertainties of such a bold new venture can wait a moment. For Whitmore, the space has been created for athletes like her to flourish, and she cannot wait to see what that will look like.

“Everything starts with a foundation,” Whitmore tells USA TODAY Sports. “Us women in baseball have been doing it on our own for so long. “And to see the people behind the scenes at the league getting involved in it like we as women have: That’s what we need. The people outside of it who are willing to step into our world and tag along.

“And now, being able to have other people see the vision we do – that’s where everything’s going to blossom, where opportunities are going to grow.

“I’ve always dreamt of it. I didn’t know if it was ever going to happen.”

The intended reality of what was once Whitmore’s dream looks like this: The WPBL will consist of a handful of ballclubs playing at one or two central sites beginning in May 2026. Games will be Thursday through Sunday, the better to fit players’ schedules and appeal to fans.

Players will be paid within a salary structure determined by their selection in the draft, with a revenue-sharing program based on the league’s sponsorship income. Committed players include former Little League World Series star Mo’ne Davis, back on the diamond after a college softball career at Hampton, and Olivia Pichardo, the first woman to play in a Division I college game, for Brown.

Co-founder Justine Siegal also founded Baseball for All, a girls baseball organization whose annual national tournament recently marked its 10th anniversary; fellow co-founder and chief investor Keith Stein, like several key members of the organization, hails from Canada, where, along with Japan, women’s baseball flourishes in a manner never seen in the USA.

Chair Assia Grazioli-Venier is a venture capitalist who has invested in the NWSL’s Washington Spirit and the sports vertical Just Women’s Sports.

It is all very ground-floor at the moment, lacking, for better or worse, the financial backbone and overlord status the NBA lent to the WNBA for its 1997 launch.

Eventually, success will be measured by attendance and cultural currency and, perhaps, TV ratings. For now, Whitmore only sees one significant triumph: A destination for young, talented ballplayers.

“Success within it is allowing them to not go through what I went through when I was younger, which was not knowing what path to take to do what I loved,” says Whitmore. “There was no path. There was no direction.

“I had to create the path, create the direction.”

Detours and destiny

For Whitmore, that meant staying on the diamond by any means necessary. She played, and flourished, on her baseball team at Temecula Valley High School, a baseball-rich exurb an hour north of San Diego.

Yet finding a place to play collegiately, even a small-college option like former pitcher Ila Borders was able to find in the 1990s, proved elusive.

So she, like Davis, accepted a softball scholarship, to Cal State Fullerton. By her senior year in 2021, Whitmore was the Big West Conference’s player of the year, with a .395/.507/.824 slash line.

Yet the lack of an outlet forced Whitmore into bifurcating her talents in order to get her education paid for, as she was forced to shelve pitching for most of those years. She hopes more former baseball players gravitate back to the big diamond.

“I had to play softball in college, unfortunately,” she says. “I did not want to. It was just where my path led me to. I wouldn’t change it. But there’s a lot of girls that grew up playing baseball but transitioned into softball.

“I think those girls that grew up playing the game of baseball still have a lot of passion for it and can coexist with us women who are in baseball. And I think they should.

“They had a lost opportunity a while back and maybe if they came back to it, they’d fall back in love with it again.”

Yet Whitmore’s precocious ability enabled her to stay in it. She first earned a spot on the USWNT in 2014, when she was 16. By 17, she joined Stacy Piagno as the only women on the roster of the short-season independent league Sonoma Stompers, spending two summers playing against men a decade her senior.

After college, another opportunity presented itself: The Staten Island FerryHawks, members of the independent Atlantic League, offered Whitmore a shot.

She’d be the first woman since Borders to play at such a high level, and the first to play in a Major League Baseball-affiliated indie league after the minor leagues were reorganized.

Whitmore spent two seasons with the FerryHawks, the challenges between the lines and beyond both significantly challenging. She had one hit in 54 at-bats, and in 24 appearances on the mound gave up 27 earned runs in 22 ⅔ innings.

She found more success playing pro ball in Mexico but noted that “they weren’t ready for a woman.” She opted to end a stint with the independent Oakland Ballers after one season.

It was equal parts invigorating, intimidating and isolating.

“Sonoma, Staten Island, the Ballers and Mexico – all of it I’m thankful for,” she says. “I loved each one, but there were also times it was really lonely. Like, really lonely. It was scary sometimes. It was hard. It made me really crave being able to be on a team full of women.

“I didn’t feel like I could be myself as a player and a person. Not that anyone made me feel that way. But you’re trying to compete and keep your spot and not get cut and trying to prove yourself. It felt like a lot of pressure over the years, but I learned so much. And I was surrounded by a lot of great players. I would not take it back one bit.

“I just made a hundred more brothers than I had before.”

She emerged just a little disillusioned, yet the perfect vehicle to discover her joy for the game was just around the corner.

Going Bananas

When Whitmore opted not to rejoin the Ballers for a second season, she was sans team. A year earlier, though, the Savannah Bananas had reached out, inquiring about her services.

Figuring their vaudevillian brand of Banana Ball was just a little too unserious, she declined. Yet by this year, she was ready to join the circus.

“When they called, it was a sign that maybe, instead of me chasing all these teams that aren’t wanting me the way I want them, the Bananas wanted me for me,” she says. “That really hit me. I was like you know what? I’m gonna take a chance on it.”

At the least, she says, it enabled her to fulfill some dreams, such as playing in big league ballparks, in front of overflow crowds, even. Come September, she’ll play at the ballpark of her youth when the Bananas visit Petco Park for a two-night gig.

And she knew she made the right decision on Aug. 15, when Bananas founder and owner Jesse Cole approached her in the Chicago White Sox clubhouse with a message before taking the field.

“He says, ‘Listen, I want you to have fun out there. People know you’re having fun, they’re having fun, too,” she recalls. “Because I’m very serious, I put pressure on myself, I get mad at the little things, I take the game so seriously.

“He says, ‘You’ve already won being out there. You don’t have to prove yourself anymore. Just go out there and enjoy it.’

“I had a really good inning and I had fun and I felt the most me out there.”

And it is not like the baseball is bad. The Bananas feature former professional and collegiate players, mixed in with regionally-appropriate MLB alum cameos, such as White Sox lefty Mark Buehrle, who at 46 worked an inning in Chicago with old batterymate A.J. Pierzynski.

Whitmore recently induced three ground balls in an inning of work, all of them to a shortstop who performed some form of acrobatics in converting all three into routine outs.

“It’s making me be more creative and honestly, helping me be more me, as a player,” she says. “That’s something I’ve always felt more restricted to in conventional pro ball, where it’s like, ‘Hey, you can’t throw 90? Well, we need you to train in the offseason to get as close as you can to 90,’ and that’s all they want. Velo, velo, numbers, numbers. It’s trying to fit this cookie cutter.

“With Banana Ball, they don’t want you to be cookie cutter. They want you to come as yourself and be as you as you can and compete. And have fun.”

Time to ball out

That freedom has allowed Whitmore’s mind to wander when it comes to what the WPBL can become. She envisions the league hub as a place where a loyal, local following can be developed, along with a destination for out-of-towners to visit for a game.

She hopes the USWNT can, through the WPBL, develop more cohesion as a unit, since they’d be playing together or against one another, rather than convening biannually. That should only enhance their chances of breaking Japan’s stranglehold on the Women’s World Cup gold medal, which they’ve won seven consecutive times since the USA’s last gold in 2006.

She hopes a high quality of play will attract sponsorship and support from USA Baseball and MLB, which produces a Trailblazers Series for teen baseball players and in May partnered with Athletes Unlimited to “strategically invest” in their softball league.

And she hopes ballplayers can eventually join their sisters in soccer, basketball and tennis and “get to a point where us women in the league can make a living off this, honestly.”

It all starts this weekend, when Whitmore reconvenes with friends old and new and expects to have her eyes opened by the talent around her.

‘I’m excited to see girls that I don’t even know that show up and they’re balling out,” she says. “Women’s baseball is such a small world and we kind of all know each other. However, the ones that maybe haven’t played on the national team and I haven’t met them before – I’m excited to see those faces too. At the end of the day, it’s exciting to see how many girls love baseball and want to be a part of it.

“It gives reassurance that wow, I’m really not the only one that loves this game. It shows how powerful women in baseball are. We’ve been here, it’s just that now, we’re finally being seen.”